This is the eighth in a series of articles chronicling the events from May 1660 through January 1661, commemorating the 350th anniversary of the Restoration of the English monarchy, the reopening of the playhouses, and the first appearance of an actress on the English stage. You can find links to the other articles on my website, gillianbagwell.com.

DECEMBER 1660

December 1660 was the seventh full month of Charles II’s reign after he had ridden into London on May 29, his thirtieth birthday, to reclaim his throne after years of exile. The enormous task of reestablishing the monarchy and its new government continued.

Parliament was still busy, trying to wrap up business before Christmas. Seven new bishops were consecrated in Westminster Abbey on December 2, and a royal commission composed of some of the king’s most eminent ministers was formed to address the problem of land that had changed hands during interregnum.

Dealing with those who had been responsible for the trial and execution of Charles I was still front and center. A man named Tench, who had built the scaffold on which the king was executed, was arrested. After an ugly series of executions in October, the king had stayed the sentences of the remaining regicides. They still sat in prison, their lives in the balance, and Parliament set up a committee to consider their fate. Even those who were dead were not safe from retribution. On Friday, December 7 the Commons passed a resolution “that the carcasses of Oliver Cromwell, Henry Ireton, John Bradshaw, and Thomas Pride, whether buried in Westminster Abbey or elsewhere, be with all expedition taken up, and drawn upon a hurdle to Tyburn, and there hanged up in their coffins for some time, and after that buried under the said gallows.” On Monday, December 10 the Lords agreed it should be so.

Paying off the crews of the navy’s ships was another ongoing headache. As secretary of the Navy Board, the temperamental diarist Samuel Pepys was very much involved in this work. But he began the month by beating his maid. “Observing some things to be laid up not as they should be by the girl, I took up a broom and basted her till she cried extremely, which made me vexed, but before I went out I left her appeased.”

Pepys then turned his attention to “the growing charge of the fleet.” On December 3 he met with his colleague Sir George Carteret, who proposed paying the sailors half what they were owed, and giving them tickets vouching that they would be paid the other half in three months. The next day they met with the Duke of York, who was also the Lord Admiral, who approved “paying them in hand one moiety and the other four months hence” – the poor sailors were getting a worse deal each day - so Pepys and Carteret drew up the plan to be presented to Parliament.

On December 6, Pepys spent a pleasant evening at an alehouse near Parliament Stairs with several companions, “among the rest one Mr. Pierce, an army man, who did make us the best sport for songs and stories in a Scotch tone (which he do very well) that ever I heard in my life. I never knew so good a companion in all my observation. From thence to the bridge by water, it being a most pleasant moonshine night, with a waterman who did tell such a company of bawdy stories, how once he carried a lady from Putney in such a night as this, and she bade him lie down by her, which he did, and did give her content, and a great deal more roguery.”

On December 9 Pepys sadly recorded that the ship Assurance at Woolwich “was by a gust of wind sunk down to the bottom. Twenty men drowned … and I am sent to the Duke of Yorke to tell him.” The Duke went to inspect the wreck the next day, and on December 11, “though the weather was very bad and the wind high,” Pepys and his wife, along with Lady Batten and her maid “did go by our barge to Woolwich (my Lady being very fearfull) where we found both Sir Williams and much other company, expecting the weather to be better, that they might go about weighing up the Assurance, which lies there (poor ship, that I have been twice merry in, in Captn. Holland’s time,) under water, only the upper deck may be seen and the masts. Captain Stoakes is very melancholy, and being in search for some clothes and money of his, which he says he hath lost out of his cabin.”

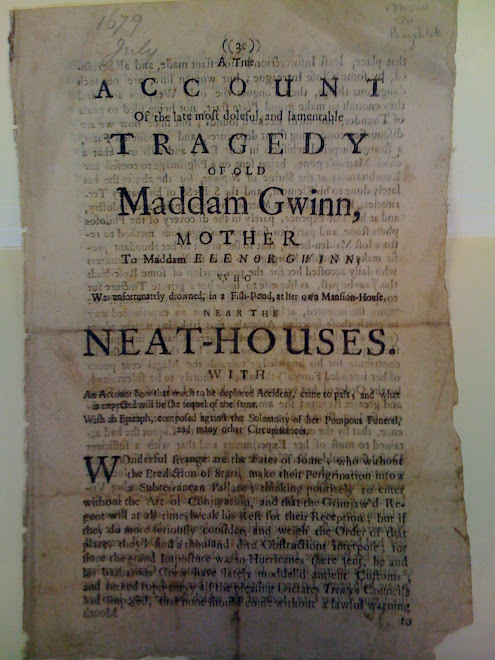

The saga of the Duke of York and Anne Hyde was winding down. On Sunday, December 9 their son James was christened at Worcester House, the home of his grandfather Edward Hyde, with the king, Prince Rupert, and the Duchess of Albemarle serving as godparents. Pepys was behind on the news, as on December 10 he wrote “it is expected that the Duke will marry the Lord Chancellor’s daughter at last which is likely to be the ruin of Mr. Davis and my Lord Barkley, who have carried themselves so high against the Chancellor; Sir Chas. Barkley swearing that he and others had lain with her often, which all believe to be a lie.” On December 16 Pepys heard “that all is agreed and he will marry her. But I know not how true yet.”

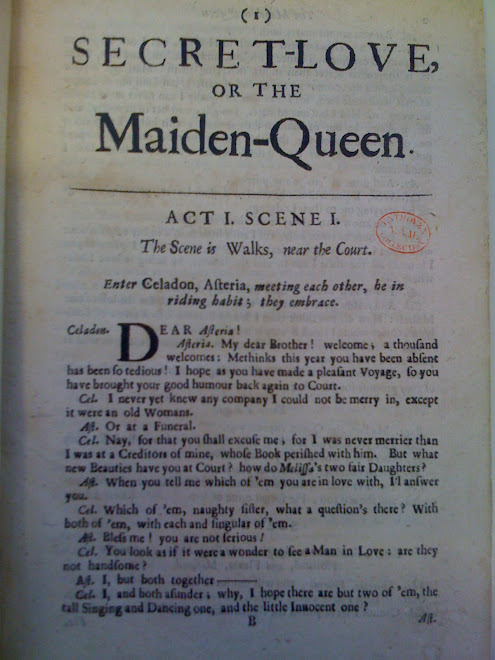

The King’s Company was drawing crowds at their new theatre, playing The Alchemist, Claricilla, A King and No King, Rollo Duke of Normandy, and repeats of The Silent Woman. On December 5 Pepys wrote “after dinner I went to the new Theatre and there I saw ‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’ acted, the humours of the country gentleman and the French doctor very well done, but the rest but very poorly, and Sir J. Falstaffe as bad as any.”

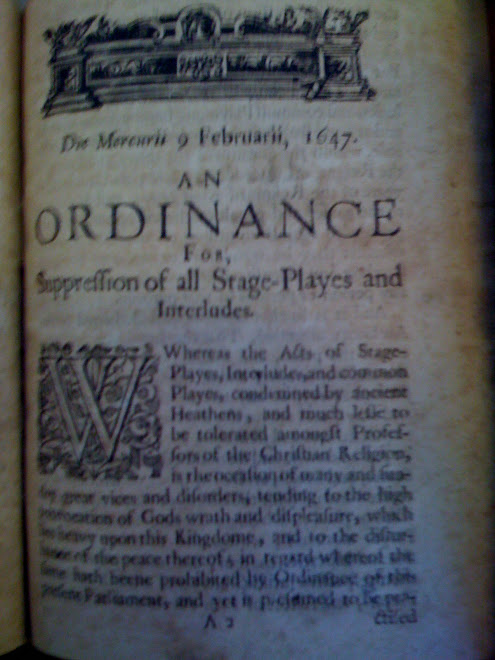

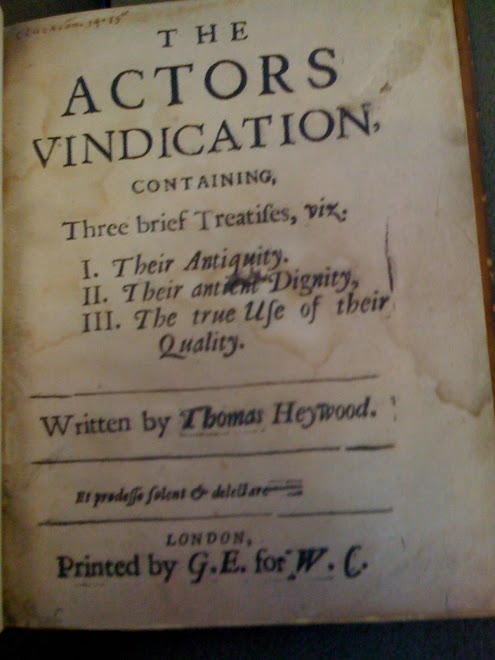

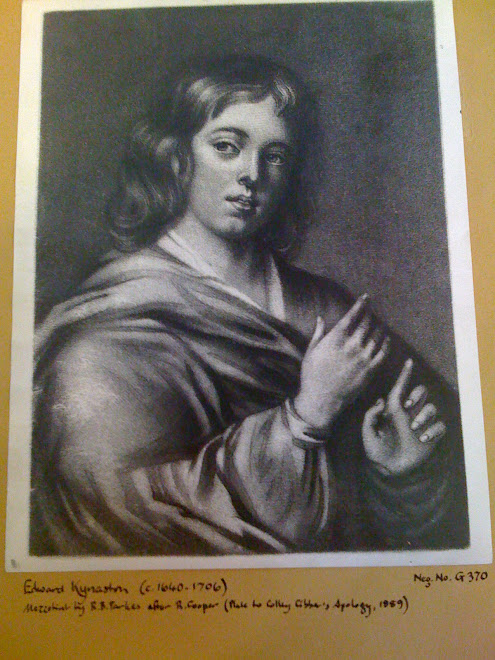

On December 8, a momentous event in theatre history took place when an actress, likely Anne Marshall, played Desdemona in Othello (The Moore of Venice). It was the first time that a woman had woman had appeared on an English stage, and the occasion was marked by a special prologue.

On December 12, William D’Avenant at the rival Duke’s Company was granted a warrant to present The Tempest, Measure for Measure, Much Ado About Nothing, Romeo and Juliet, Twelfth Night, The Life of King Henry the Eighth, King Lear, Macbeth, Hamlet, The Sophy, and The Duchess of Malfi, as well as his own plays. He also got exclusive rights for two months to The Mad Lover, The Mayde in the Mill, The Spanish Curate, The Loyall Subject, Rule a Wife and Have a Wife, and Pericles, Prince of Tyre. It is interesting with modern perspective to note that when D’Avenant and Killigrew divided up the rights to Shakespeare’s plays, D’Avenenant was considered to have gotten the short end of the stick.

On December 13, diarist Elias Ashmole recorded that “The king going to a play at the new Theatre this afternoon …the leathers whereby the coach hung broke and so the coach fell from the wheels … overturned over against the new Exchange but (blessed be God) had no hurt.”

There was another conspiracy against the king’s life. On Sunday, December 16, Pepys went “in the morning to church, and then dined at home. In the afternoon I to White Hall, where I was surprised with the news of a plot against the King’s person and my Lord Monk’s; and that since last night there are about forty taken up on suspicion.” The king took part in examining the accused, but nothing much seems to have come of the episode.

Parliament was to have been dissolved on December 20, but there was much business remaining, so it was decided they would adjourn on December 23, meet again after Christmas, and the dissolution would take place on December 29. The members must have been getting restless, as on December 14, Serjeant Maynard moved that the Speaker should reprove anyone he observed talking, whispering, or reading a paper. A bill for setting up a general letter office was read for the third time. There was a proviso allowing Cambridge and Oxford to continue to carry their own letters, and after fierce argument as to which should be named first, the Commons finally settled on referring to “both universities.” Edward Hyde had been made chancellor of Oxford, succeeding Cromwell.

Parliament settled a regular income on the king, approved £70,000 for the expenses of the coronation, including the provision of new crown jewels, and awarded gifts of £1000 each to two people who had risked their lives to help Charles escape after the Battle of Worcester in 1651 – Jane Lane, who had disguised Charles as her manservant and traveled with him for ten perilous days, and Francis Wyndham, who had hidden them at Trent.

In Seething Lane, Samuel Pepys was cracking the whip to get his home improvements done. On December 13 he spent “All the day long looking upon my workmen who this day began to paint my parlour,” and did the same on December 14 and 15. On December 17 he once more spent “all day looking after my workmen…. This day my parlour is gilded, which do please me well.” Still, the next day two days he was he “looking after my workmen.” On December 20 he wrote, “All day at home with my workmen, that I may get all done before Christmas.”

But his entry continued with more serious news. “This day I hear that the Princess Royal has the small pox.” On December 21, Pepys heard “how dangerously ill the Princess Royal is and that this morning she was said to be dead.” It was only a little more than two months since the king’s youngest brother, the Duke of Gloucester, had died of smallpox, and everyone recognized the graveness of the Princess Mary’s illness. The king’s sister made her will, commended her son William of Orange to the care of the king, and apologized for her treatment of Anne Hyde.

On December 21, diarist John Evelyn wrote “The Marriage of the Chancellor’s Daughter being now newly owned, I went to see her … she now being at her fathers, at Worcester house in the Strand, we all kissed her hand, as did also my Lord Chamberlaine …and Countesse of Northumberland: This was a strange change, can it succeed well!” He spent the evening at St. James’s Palace, where he heard that the King’s youngest sister, Minette, had been moved there to be out of harm’s way.

By December 23, Mary seemed better. But on December 24, when Pepys was happily “with the painters till 10 at night … and my house was made ready against to-morrow being Christmas day,” he concluded his entry, “This day the Princess Royal died at Whitehall.”

As Evelyn recorded, her death “wholly altered the face and gallantry of the whole court.” The stunned King secluded himself. Queen Henrietta Maria, devastated at the loss of another child, swore that staying in England would end her days, and made plans to return to France on January 2. On Christmas Day, Evelyn heard a sermon at Westminster Abbey “condoling the breach made in the publique joy, by the lamented death of the Princesse.”

It was a sad day for the royal family and for the court, but in general, 1660 saw a happier Christmas in England than for many years. Under Cromwell, the day had been one of fasting and atonement, but now the old festivities were revived. Pepys was “In the morning very much pleased to see my house once more clear of workmen and to be clean, and indeed it is so, far better than it was that I do not repent of my trouble that I have been at,” and he had guests to dinner “to a good shoulder of mutton and a chicken.”

On the day after Christmas, Pepys dined at White Hall with Lady Sandwich, the wife of his patron, “who at table did tell me how much fault was laid upon Dr. Frazer and the rest of the Doctors, for the death of the Princess!”

Mary’s funeral was held on Saturday, December 29 at Westminster Abbey. Her brother the Duke of York walked behind the coffin, and the procession passed through the ranks of the Coldstream Guards, one of only three regiments remaining after the steady disbanding of the army.

On the same day as Mary’s funeral, King Charles came out of his seclusion to dissolve the Convention Parliament. The work of establishing his government was done, and there would be elections for a new parliament in the new year.

Pepys had begun his famous diary on the first day of 1660. It had proved to be a productive and golden year for him, and on December 31 he treated himself with a little entertainment. After spending the morning at his office, “In Paul’s Church-yard I bought the play of ‘Henry the Fourth,’ and so went to the new Theatre … and saw it acted; but my expectation being too great, it did not please me, as otherwise I believe it would; and my having a book, I believe did spoil it a little."

Tuesday, January 25, 2011

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment