On Thursday I went to Westminster Abbey, where the coronation of Charles II took place, as well as that of his brother James II, and all other Kings of England since 1066 except Edward V and Edward VIII, who didn’t have coronations.. The coronation chair built by Edward I was there, which has been used for all coronations since 1308 except that of Mary I.

Nell would not have been at the coronation, but the legend is that she was at Charles’s funeral, standing at the back, and that when everyone else had gone, she laid flowers on his coffin and said her last goodbyes to her lover of seventeen years and the father of her two children.

She may also have been at Westminster Abbey for the christening, and then the sad little funeral a few months later, for the son of her good friend George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham. The baby was Buckingham’s child by his mistress, Anna Maria, Countess of Shrewsbury, whose husband Buckingham had fatally wounded in a duel. Though the baby was illegitimate, Buckingham bestowed on him one of his own hereditary titles, Earl of Coventry. The title wasn’t really his to give, but since the orphaned Buckingham had been taken in by Charles I and raised more or less as a brother to Charles II, perhaps the King didn’t raise a fuss.

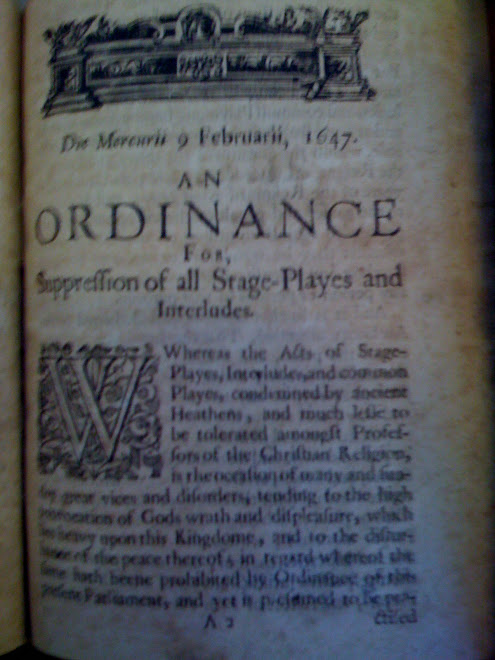

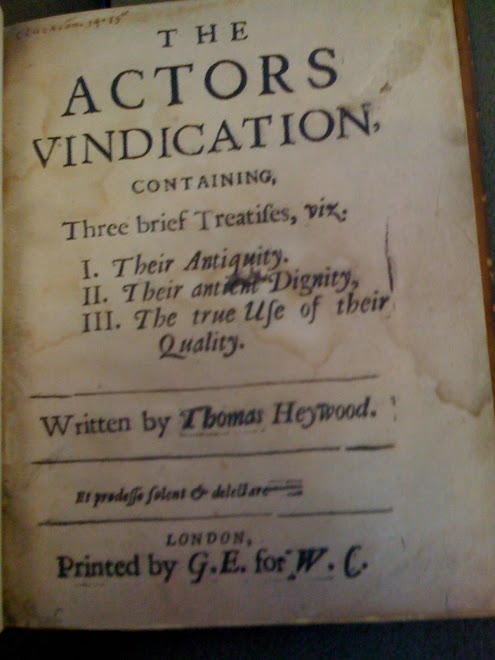

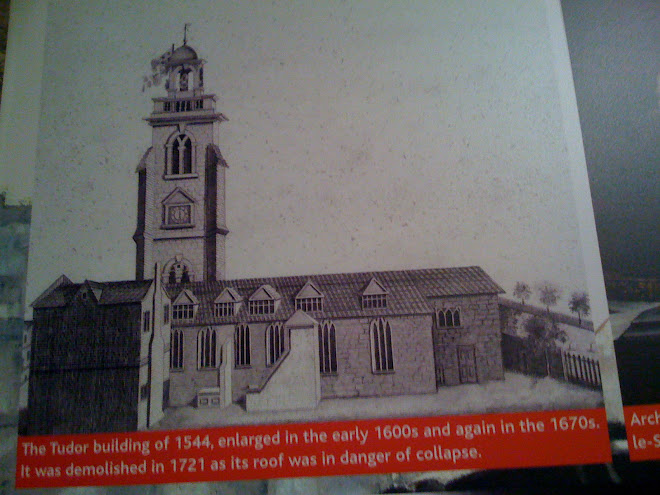

Later on Thursday, I went in search of the Red Bull Theatre on St. John Street in Clerkenwell. The theatre, an open air enclosed yard like the Globe, was built in about 1604. It survived the Commonwealth (and some clandestine performances were given there during those years), and in 1660, when Charles authorized the reopening of the theatres, Thomas Killigrew’s King’s Company gave a few performances there before moving to their new home in Lincoln’s Inn Fields.

According to a contemporary map, Red Bull Yard, presumably leading to the playhouse, was located about 100 feet north of Clerkenwell Road. As near as I can determine, this means that the theatre was situated roughly on St. John’s Square, a pleasant open area just behind St. John’s Church. There’s been a church of some kind there for about 900 years, but according to the London Encyclopedia, Elizabeth I gave the use of the buildings to the Master of the Revels, and it appears that the site was not used as a church during the period in which the Red Bull was at its height, so it seems possible that the theatre could have directly adjoined the church. In any case, it was certainly in the area that is currently bounded by St. John’s Street on the east, Albermarle Way on the south, St. John’s Square on the west, and Aylesbury Road on the north. One source says it was in what is now Woodbridge Street, but that seems just a tiny bit too far north.

On Friday, I set out for Lincoln’s Inn Fields, where the first two new theatres opened after the Restoration, and where Nell lived for a time.

The Vere Street Theatre, occupied by the King’s Company, and the Duke’s Company, managed by Sir William Davenant, were in converted tennis courts. This may seem unlikely, but a tennis court was probably an ideal kind of building to use for a playhouse – it would have had a large open area in the center, surrounded by galleries for spectators, and rooms at either end that could be used for dressing rooms and/or a lobby. And in 1660, Lincoln’s Inn Fields had only recently been developed with houses and was a fashionable area.

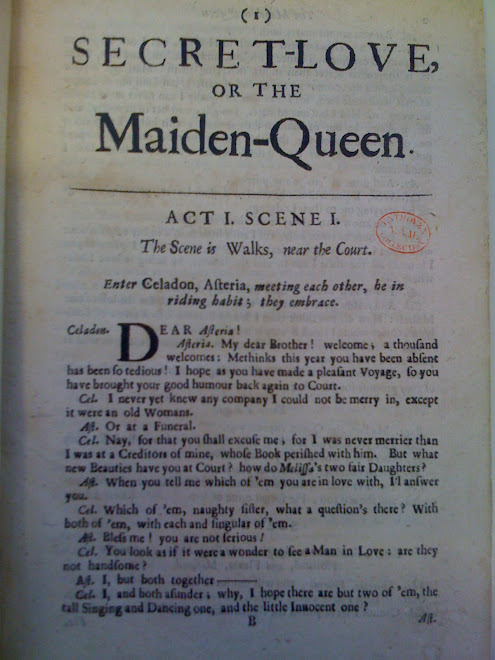

Sir Thomas Killigrew and the King’s Company opened their theatre first, on Thursday, November 8, 1660, with a performance of “Henry IV, Part One,” in what had been Gibbons’ Tennis Court. It was a fashionable place already, with grounds including a tavern and coach houses. The site is shown on Newcourt’s map of 1658, Hollar’s map of 1657, Lea and Glynne’s map of 1706 and others. The entry was from Vere Street (no longer there, and replaced by Kingsway), and bounded by Duke Street (now Sardinia Street) to the north, Sheffield Street to the south, and Portugal Row to the east.

As with much of London, the current streets lie pretty much as they did centuries ago, and there is still a little plot of land within those bounds, just southwest of the southwest corner of Lincoln’s Inn Fields, which includes the Peacock Theatre, Sardinia House, a pub, and two brick buildings possibly of Victorian vintage, which are identified as St. Philip’s Building South Block and St. Philip’s Building North Block of the London School of Economics. There is a narrow walkway between the two buildings leading to some stairs down into a dank below-ground yard that I think is probably about where the theatre itself stood.

Lisle’s Tennis Court, where the Duke’s Company performed beginning in June 1661, is only about a hundred yards or so from the site of Killigrew’s theatre, on the north side of the T-intersection between Carey Street and Portugal Street. What stands there now is part of the very large building that houses the Royal College of Surgeons. There is a door into the building just at the intersection. A Russian gentleman who saw me taking pictures and asked what was significant about the area told me that that part of the building had been a morgue until 2003, that it had been bought by the London School of Economics (!) and was now used as classrooms, and that it still smelled!

The Earl of Rochester had a house next door to the theatre, and the actors used to drink at the Grange Inn a few yards south of the theatre, presumably in Carey Street. Hollar’s map of 1657 shows the tennis court sticking out into Lincoln’s Inn Fields, the last building on the east end of Portugal Street, and a tiny coach sitting outside the Grange Inn.

There continued to be a theatre on this site for many years. It was there that “The Beggar’s Opera” first played.

In 1669, Charles moved Nell into a house in Newman’s Row, just off the northeast corner of Lincolns’ Inn Fields. Newman’s Row is now barely more than a walkway leading up to Holborn, with a modern building on the east side and construction going on to the west. Now, it joins up with the walkway along the east side of the square. When Nell lived there, however, the street was separated from the square by a swathe of land that on Hollar’s 1658 map appears to be about 100 feet wide or so and with greenery. And the east end of Whetstone Park, an unsavory and crime-plagued narrow street running east to west between Holborn and Lincoln’s Inn Fields, ran into Newman’s Row. So though Nell’s house was technically at Lincoln’s Inn Fields, it wasn’t in the fashionable or best part, and after she bore the King their first son, she talked him into a better house on Pall Mall.

Nell’s house in Newman’s Row was only about a ten-minute walk from the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane and the Covent Garden area, though a world away from the slums north of Covent Garden where she grew up. She only acted in one play after having her first child, but went to plays frequently at both the King’s and the Duke’s Companies.

I walked back to Covent Garden to find some more Nell-related sites. Her mother kept bar, and she also worked, at the Rose and Crown in Russell Street. She would certainly have known Will’s Coffee House, in Bow Street, and the Rose Tavern, in Russell Street next to the Theatre Royal.

Charles Hart, the leading actor of the King’s Company and Nell’s lover and mentor, had lodgings at the northeast intersection of Russell Street and Bridges Street (now Catherine Street), probably roughly where the pub the Marquess of Anglesey sits now.

Also in Drury Lane was the Cockpit, another Jacobean era theatre that survived the Commonwealth and was used for some unauthorized performances during that time. It sat in the roughly triangular area bounded by Drury Lane to the southwest, Green Queen Street to the north, Wild Street to the northeast, and Princes Street (now Kemble Street) to the southeast. As with the other old theatre sites, there is a pub still on the grounds and the layout has probably not changed. The theatre was probably more or less at the site of 141 Drury Lane, where there is now a building occupied by – wait for it – the London School of Economics!

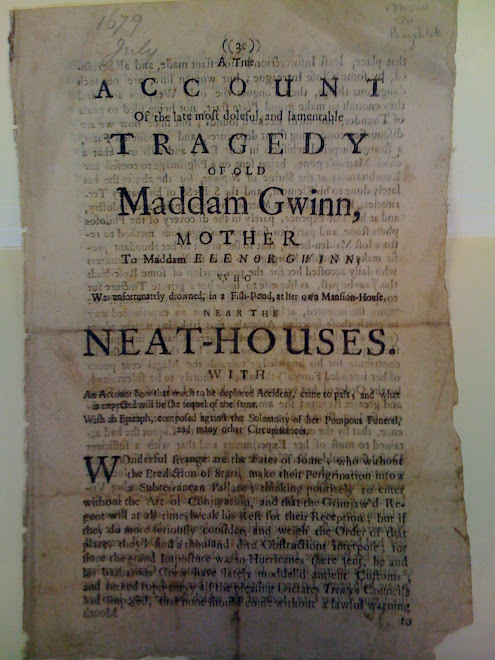

I wandered around the little streets north of Covent Garden, which are now full of fashionable shops, pubs, and restaurants, but in the seventeenth century could be dangerous places. In 1679 the playwright John Dryden was attacked in Rose Street on his way home from Will’s, possibly at the behest of the Earl of Rochester. It’s little more than an alleyway a hundred feet long or so, narrow and twisting, and it would only take an armed man at each end to make it an effective trap.

Next I headed east along the Strand and Fleet Street to find the sites of two more theatres, Salisbury Court and the Dorset Gardens. Salisbury Court was another survivor from the early 17th century, but was an indoor playhouse, and Davenant’s Duke’s Company performed there before moving to Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The theatre would have been roughly where Salisbury Square sits now, a little south of Fleet Street, and on the east side of the KPMG building at No. 8 Salisbury Square, there is a plaque stating that the theatre stood there.

As Salisbury Street runs south, it runs uphill slightly and turns into Dorset Rise, a narrow street that slopes down toward the river. In 1674, the Duke’s Company opened the very grand new Dorset Gardens Theatre, which sat right on the river, due south of St. Bride’s church. Fashionable audiences would have frequently traveled to the theatre by water, and Ogilby and Morgan’s map of 1677 shows boats crowded around the landing steps leading from the water up to the theatre. Their map of 1681-82 labels not only Dorset Stairs as well as the nearby Blackfriars Stairs and Whitefriars Stairs.

This area is much changed from the seventeenth century. Blackfriars Bridge crossed the river from here, Queen Victoria Street leading to Victoria Embankment is a busy street, and there are steps leading down to the equally busy Blackfriars Underpass. But the Dorset Gardens Theatre would have been just about on the site of the very grand building that sits just to the west of 100 Victoria Embankment. It’s probably best viewed from the river.

Well, it's Monday evening and I still haven't caught up and now my buddies are arriving for a last night at the Nelson. So, more to come.

A final note about London today - last Friday I noticed three guards outside the Canary Wharf office of Lehman Brothers, its European headquarters. I passed by about noon today, and guards had been replaced by police - and a whole phalanx of photographers. And yes, unfortunately, I owned some Lehman stock. Good thing I have a pint in front of me, friends around me, and I'm going home tomorrow!

Monday, September 15, 2008

Friday, September 12, 2008

Windsor, Epsom, the Gunmaker’s Lunch, Samuel Pepys, The Lord Nelson Pub Quiz, Lots and Lots of Very Old Maps

Oh, dear, oh, dear – once more I’ve been racing around getting a lot accomplished but not finding the time to write about it! So here goes…

WINDSOR

Last Saturday, Alice and I went to Windsor, where Charles II and his court spent quite a lot of time, and Nell did, too. We found her original Windsor residence, a townhouse a couple of hundred yards outside the castle walls, part of it now occupied by the rather incongruously named Nell Gwynn Chinese Restaurant. (Update, July 21, 2013: I had an email from Rob Abell, who tells me: "I am reliably informed by my Windsor historian friend, Elias Kupfermann, that the Chinese restaurant you refer to has no connections to Nell Gwyn whatsoever. I asked the restaurant to remove their misleading plaque. Unfortunately we have had a number of businesses all claiming to have been home to Nell Gwyn, so have had to sort these out!")

Later, Nell lived in (and in 1680 was given the freehold of) Burford House, a grand house on the palace grounds. Unfortunately, Burford House is a private residence and not open to be viewed, but we did our best by peeking in at the gate that is only about 75 feet from its door. From the upper floors, Nell would have had spectacular views to the southeast over Windsor Great Park, and of the castle and maybe the river looking to the north and west. The pretty and ancient St. John’s Parish church is just across the road from her house.

When Nell and Charles’s younger son James died at the age of eight in June 1680, Charles encouraged her to find solace in redecorating Burford House. They spent the summer in Windsor, and among other things, she commissioned paintings on the ceilings by AntonioVerrio, an Italian who was a favorite among the English upper class and did extensive painting for Windsor Castle, among other places.

The court traveled between Windsor and London by water (Purcell used to write little welcome-home songs for Charles), and Alice and I walked along the banks of the Thames, which is narrow and meandering at that point, its grassy banks overhung by trees, and probably not much changed from Nell’s day. Eton is just over the bridge.

A few streets grew up centuries ago just outside the castle walls, and their layout appears to have remained much the same. On the high street just outside the palace gates there is a grand red brick Guildhall designed by Christopher Wren, and it was there that Prince Charles and Camilla got married in 2005 when it was discovered that if they had a civil service in the castle’s St. George’s Chapel, the chapel would have to be opened for public use as a place to get married! One of my favorite headlines from that week was the local paper’s deadpan “Tetbury Man to Wed.”

EPSOM

On Sunday, Alison drove me to Epsom. In spring 1667, Charles Sackville, Lord Buckhurst was “inflamed” by seeing Nell’s performance in “All Mistaken,” in a breeches role that allowed her to show off her legs. He convinced her to leave the stage, and she went with him and his friend Sir Charles Sedley to Epsom.

Epsom had recently become a fashionable retreat from London for the upper crust, both for the healing qualities of the waters, and because of the newly-introduced racing at Epsom Downs (though it was not until 18th century that the Derby was so named).

Samuel Pepys was staying at the King’s Head next door to where Nell was living with the boys, and commented that they kept “a merry house.” I’ll bet they did. Whatever the arrangements were, they didn’t last long, and by late August Buckhurst had thrown Nell out and she had to slink back to London in shame and ask to be taken back at the theatre.

To my delight, Ye Olde King’s Head is still there, on what is now Church Street, and was formerly the high street of Epsom. It was built in the mid-16th century, and the inn next door, no doubt where Pepys stayed, was built in the early 17th century. It appears that whatever house Nell lived in is probably gone, but the road is quiet and rural, with a church and churchyard across the road, parts of which date from the 12th century, and it’s easy to image what a lovely location it must have been to spend a couple of summer months, especially for Nell, who wouldn’t have had much experience of anything but the noise and crowding of London.

The King’s Head was offering the traditional Sunday lunch, and I was served about half of a lamb with a pile of potatoes; a big dish of carrots, cabbage, broccoli, and parsnips; mint sauce; and gravy. Alison, a veggie, ordered the lunch without the meat, and still had a pile of food, including a Yorkshire pudding.

SAMUEL PEPYS

On Monday, Alice and I went to the church of St. Olave Hart Street for one of a series of lectures that is being given throughout the year on 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys, who headed the Naval Office and knew Nell as well as the King, the Duke of York, and many other prominent people of the time. He lived and worked across from the church in Seething Lane, and is commemorated with a bust in the small Pepys’s Park there.

I was a bit disappointed in the lecture, as there wasn’t much about the subject on which Pepys and Dryden had the most in common – theatre. But it was an interesting evening, and good to see the little church again. There is a monument high on one wall near the pulpit (stage right, so to speak) that Sam had put there when his wife Elizabeth died. The vicar, Oliver Ross, explained that the monument would have been visible to best advantage from the Naval Pew, where Sam sat. The pew is gone, but there is now a monument to Pepys himself in the wall where the exterior door to the upstairs pew would have been located. So when Sam came into the church in life, he was walking through what would later be his own headstone! The vicar also commented that if you stand on something high to get the view of Elizabeth’s monument that Sam would have had, her dress appeared more diaphanous than it does from floor level.

The good vicar was also much interested in the outcome of the presidential election, as are many other Britons, and we commiserated a bit about the prospect of Sarah Palin in the White House.

LUNCHEON AT THE WORSHIPFUL COMPANY OF GUNMAKERS

On Tuesday, I had the pleasure of attending a lunch given by the Worshipful Company of Gunmakers, of which my friend Donna is a liveryman (no liverywomen) by virtue of her work with firearms in her capacity as a senior metal conservator for the Victoria & Albert Museum.

I received a gilt-edged invitation with my name and the details of the event in calligraphy, and a letter with the company’s coat of arms stating that there would be a tour of Proof House before lunch for anyone interested.

A charming man whose bearing made it a sure bet he was ex-military showed us around the premises. I didn’t know quite what to expect (cannons? flintlocks?) but it turns out that the Gunmakers are responsible for proofing, or testing, the fireworthiness of all guns and firearms in Britain – including every weapon used by the armed forces. So hundreds of thousands of modern automatic weapons go through Proof House, and they are also responsible for the modern equivalent of cannons, artillery and ship-mounted guns.

The Gunmakers also prove civilian arms, such as rifles and shotguns for hunting. An interesting piece of information is that it is legal to be carrying a firearm as long as you are on your way to or from taking it to Proof House to be tested! Also, the Gunmakers at Proof House are entitled to carry any firearm at any time, without a special license!

We were shown the testing chambers, where weapons are placed to be fired remotely into bullet-catchers. I got to do the honors of pulling a string outside the door and firing a 12-bore, which produced an enormous bang and a satisfyingly smoky room when the door was opened.

The clerk summoned us from champagne on the courtyard by banging a gavel and calling us in, and the company (about twenty people, including only one other woman besides Donna and me) sat down the long table. The room was hung with the coats of arms of past masters of the Gunmakers. The masters of the Salters’ and Blacksmiths’ companies were also present, they, like the master of the Gunmakers’ wearing elaborate badges of office on ribbons around their necks. I felt like Nell must have done, surrounded by a rather august crowd of London’s elite and mostly grey-haired gentlemen. Though as I have previously commented, though I am not one of them, I probably seemed - and felt - less out of place than an East Ender with a Cockney accent would.

I felt even more like Nell must have done in an exchange with one of the gents. In response to his jocular comment that though I probably couldn’t believe it, he was over 60, I said surely he couldn’t be more than 29. He delightedly exclaimed “Oh, good girl!” and gave my thigh a hearty squeeze.

The food was great, and the wine flowed – champagne, white wine, red wine, more white wine, dessert wine, and port served with the various courses. So I staggered back to Tim’s, where I’m staying now until I leave, and slept for a couple of hours.

Woke up in time to be more or less sober for quiz night at the Lord Nelson pub. When I was here in 2005-2006, I had a group of friends that coalesced around the weekly pub quiz, which we used to win on a regular basis (partly due to Donna’s formidable body of knowledge). This kind of quiz, involving trivia, science, sports, music, etc., is quite popular here. It was a great night, just like old times, with Alison, Donna, and me there for the beginning, Tim joining us partway through the quiz, and Alice coming by in time for the announcement that we had won, taking the L50 total of contestants’ one-pound entry fees.

I was especially pleased to see Spencer, who managed the Nelson during most of the time that I was here, and who, with co-quiz master John, came up with some pretty entertaining quizzes, including the legendary “During the war” round, with both of them dressed as old duffers in cloth caps and mufflers and puffing on pipes. Spencer doesn’t work at the Nelson anymore, so he was free to hang out, which we did until closing time.

When I was here before, I kept being baffled by how drunk I got on what didn’t seem a like very many beers. Then I realized that I had been thinking of “a beer” in terms of a 12-ounce American bottle. But in England I was drinking 20-ounce pints, and with a higher alcohol content than American beer. So “a beer” had roughly twice the kick I was used to.

THE BRITISH LIBRARY AND LOTS OF MAPS

On Wednesday I spent the afternoon in the Maps Reading Room at the British Library. My plans for research there were almost scuppered by having lost my wallet, including my driver’s license, a couple of weeks ago, since to get a reader’s pass, they require two different forms of ID to establish signature and address. Fortunately, though, they relented and gave me a week-long pass on the basis of my passport and a checkbook..

You can access the catalogue of materials on-line, either at the library or from afar, and request the materials you want to see. So I had quite a pile of original 17th century maps waiting for me, some in books, some in rolls, some folded into leather cases, some in giant portfolios. I’d seen some of them before, reproduced in books, but it was great to be able to look at the originals.

I wanted to get copies of some maps, and have been able to order a pretty satisfactory selection, but unfortunately, it wasn’t practical to get full copies of the big versions of two of the maps that I most wanted, because of their size and delicacy: Newcourt and Faithorne’s “An Exact Delineation of the Cities of London and Westminster and the Suburbs Thereof, Together with ye Burrough of Southwark and all the Through-Fares, Highwaies, Streetes, Lanes & Allies Within ye Same,” published in 1658, and the 1677 “A Large and Accurate Map of the City of London ichnographically describing all the streets, lanes, alleys, courts, yards, churches, halls and houses, &c., actually surveyed and delineated by John Ogilby, Esq., His Majesties Cosmographer.” The Newcourt map was a single sheet about 4 feet by 6 feet, and Ogilby’s is two sections, each of them comprised of about 25 or 30 pages of about 8x10 inches fitted together on a canvas backing, the whole thing folding to fit into a custom-made box.

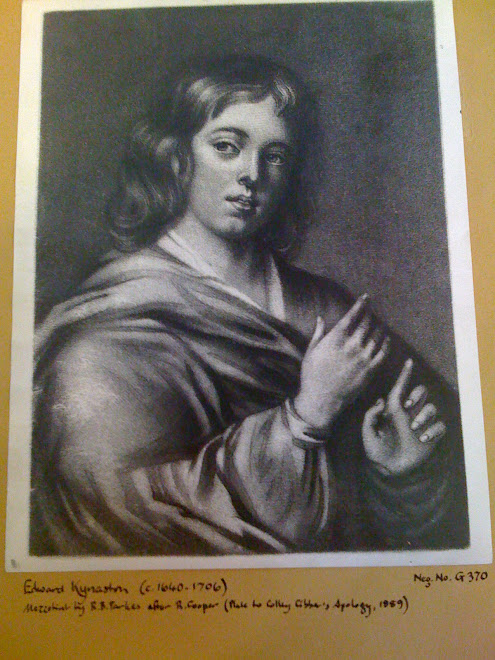

I left the British Library with my head a bit too full of tiny pictures of houses and streets, and went to the National Portrait Gallery, which includes a couple of rooms of paintings of Charles II and his family, ministers, cronies, and other contemporaries. The only picture of Nell on display is not a very good one, but there is a great portrait of her hated rival Louise de Keroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth, and another of Charles’s other main mistress, Barbara Palmer, Duchess of Cleveland, posed rather blasphemously with her oldest illegitimate son by Charles as the Madonna and child. Nearby are also Samuel Pepys, James II (then Duke of York), the unfortunate James, Duke of Monmouth, Charles II’s oldest illegitimate son, who joined in an ill-advised plot to put him on the throne and died because of it, a galaxy of other people Nell would have known.

The National Portrait Gallery has computer terminals where you can search for portraits in their collection, and can print out black and white copies for free, or order color prints of varying sizes if you want to pay for them.

I went home by way of the “River Bus,” the commuter clipper that travels up and down the river. The civilized way to commute! And related to my research, as the river was a primary mode of travel in Nell’s time. I got on the boat at the Embankment Pier, very close to the location of the Privy Stairs, where Nell would have embarked to get to Charles’s apartments.

Alright. Enough for today. I’ll try to get up to date and post some pictures tomorrow!

WINDSOR

Last Saturday, Alice and I went to Windsor, where Charles II and his court spent quite a lot of time, and Nell did, too. We found her original Windsor residence, a townhouse a couple of hundred yards outside the castle walls, part of it now occupied by the rather incongruously named Nell Gwynn Chinese Restaurant. (Update, July 21, 2013: I had an email from Rob Abell, who tells me: "I am reliably informed by my Windsor historian friend, Elias Kupfermann, that the Chinese restaurant you refer to has no connections to Nell Gwyn whatsoever. I asked the restaurant to remove their misleading plaque. Unfortunately we have had a number of businesses all claiming to have been home to Nell Gwyn, so have had to sort these out!")

Later, Nell lived in (and in 1680 was given the freehold of) Burford House, a grand house on the palace grounds. Unfortunately, Burford House is a private residence and not open to be viewed, but we did our best by peeking in at the gate that is only about 75 feet from its door. From the upper floors, Nell would have had spectacular views to the southeast over Windsor Great Park, and of the castle and maybe the river looking to the north and west. The pretty and ancient St. John’s Parish church is just across the road from her house.

When Nell and Charles’s younger son James died at the age of eight in June 1680, Charles encouraged her to find solace in redecorating Burford House. They spent the summer in Windsor, and among other things, she commissioned paintings on the ceilings by AntonioVerrio, an Italian who was a favorite among the English upper class and did extensive painting for Windsor Castle, among other places.

The court traveled between Windsor and London by water (Purcell used to write little welcome-home songs for Charles), and Alice and I walked along the banks of the Thames, which is narrow and meandering at that point, its grassy banks overhung by trees, and probably not much changed from Nell’s day. Eton is just over the bridge.

A few streets grew up centuries ago just outside the castle walls, and their layout appears to have remained much the same. On the high street just outside the palace gates there is a grand red brick Guildhall designed by Christopher Wren, and it was there that Prince Charles and Camilla got married in 2005 when it was discovered that if they had a civil service in the castle’s St. George’s Chapel, the chapel would have to be opened for public use as a place to get married! One of my favorite headlines from that week was the local paper’s deadpan “Tetbury Man to Wed.”

EPSOM

On Sunday, Alison drove me to Epsom. In spring 1667, Charles Sackville, Lord Buckhurst was “inflamed” by seeing Nell’s performance in “All Mistaken,” in a breeches role that allowed her to show off her legs. He convinced her to leave the stage, and she went with him and his friend Sir Charles Sedley to Epsom.

Epsom had recently become a fashionable retreat from London for the upper crust, both for the healing qualities of the waters, and because of the newly-introduced racing at Epsom Downs (though it was not until 18th century that the Derby was so named).

Samuel Pepys was staying at the King’s Head next door to where Nell was living with the boys, and commented that they kept “a merry house.” I’ll bet they did. Whatever the arrangements were, they didn’t last long, and by late August Buckhurst had thrown Nell out and she had to slink back to London in shame and ask to be taken back at the theatre.

To my delight, Ye Olde King’s Head is still there, on what is now Church Street, and was formerly the high street of Epsom. It was built in the mid-16th century, and the inn next door, no doubt where Pepys stayed, was built in the early 17th century. It appears that whatever house Nell lived in is probably gone, but the road is quiet and rural, with a church and churchyard across the road, parts of which date from the 12th century, and it’s easy to image what a lovely location it must have been to spend a couple of summer months, especially for Nell, who wouldn’t have had much experience of anything but the noise and crowding of London.

The King’s Head was offering the traditional Sunday lunch, and I was served about half of a lamb with a pile of potatoes; a big dish of carrots, cabbage, broccoli, and parsnips; mint sauce; and gravy. Alison, a veggie, ordered the lunch without the meat, and still had a pile of food, including a Yorkshire pudding.

SAMUEL PEPYS

On Monday, Alice and I went to the church of St. Olave Hart Street for one of a series of lectures that is being given throughout the year on 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys, who headed the Naval Office and knew Nell as well as the King, the Duke of York, and many other prominent people of the time. He lived and worked across from the church in Seething Lane, and is commemorated with a bust in the small Pepys’s Park there.

I was a bit disappointed in the lecture, as there wasn’t much about the subject on which Pepys and Dryden had the most in common – theatre. But it was an interesting evening, and good to see the little church again. There is a monument high on one wall near the pulpit (stage right, so to speak) that Sam had put there when his wife Elizabeth died. The vicar, Oliver Ross, explained that the monument would have been visible to best advantage from the Naval Pew, where Sam sat. The pew is gone, but there is now a monument to Pepys himself in the wall where the exterior door to the upstairs pew would have been located. So when Sam came into the church in life, he was walking through what would later be his own headstone! The vicar also commented that if you stand on something high to get the view of Elizabeth’s monument that Sam would have had, her dress appeared more diaphanous than it does from floor level.

The good vicar was also much interested in the outcome of the presidential election, as are many other Britons, and we commiserated a bit about the prospect of Sarah Palin in the White House.

LUNCHEON AT THE WORSHIPFUL COMPANY OF GUNMAKERS

On Tuesday, I had the pleasure of attending a lunch given by the Worshipful Company of Gunmakers, of which my friend Donna is a liveryman (no liverywomen) by virtue of her work with firearms in her capacity as a senior metal conservator for the Victoria & Albert Museum.

I received a gilt-edged invitation with my name and the details of the event in calligraphy, and a letter with the company’s coat of arms stating that there would be a tour of Proof House before lunch for anyone interested.

A charming man whose bearing made it a sure bet he was ex-military showed us around the premises. I didn’t know quite what to expect (cannons? flintlocks?) but it turns out that the Gunmakers are responsible for proofing, or testing, the fireworthiness of all guns and firearms in Britain – including every weapon used by the armed forces. So hundreds of thousands of modern automatic weapons go through Proof House, and they are also responsible for the modern equivalent of cannons, artillery and ship-mounted guns.

The Gunmakers also prove civilian arms, such as rifles and shotguns for hunting. An interesting piece of information is that it is legal to be carrying a firearm as long as you are on your way to or from taking it to Proof House to be tested! Also, the Gunmakers at Proof House are entitled to carry any firearm at any time, without a special license!

We were shown the testing chambers, where weapons are placed to be fired remotely into bullet-catchers. I got to do the honors of pulling a string outside the door and firing a 12-bore, which produced an enormous bang and a satisfyingly smoky room when the door was opened.

The clerk summoned us from champagne on the courtyard by banging a gavel and calling us in, and the company (about twenty people, including only one other woman besides Donna and me) sat down the long table. The room was hung with the coats of arms of past masters of the Gunmakers. The masters of the Salters’ and Blacksmiths’ companies were also present, they, like the master of the Gunmakers’ wearing elaborate badges of office on ribbons around their necks. I felt like Nell must have done, surrounded by a rather august crowd of London’s elite and mostly grey-haired gentlemen. Though as I have previously commented, though I am not one of them, I probably seemed - and felt - less out of place than an East Ender with a Cockney accent would.

I felt even more like Nell must have done in an exchange with one of the gents. In response to his jocular comment that though I probably couldn’t believe it, he was over 60, I said surely he couldn’t be more than 29. He delightedly exclaimed “Oh, good girl!” and gave my thigh a hearty squeeze.

The food was great, and the wine flowed – champagne, white wine, red wine, more white wine, dessert wine, and port served with the various courses. So I staggered back to Tim’s, where I’m staying now until I leave, and slept for a couple of hours.

Woke up in time to be more or less sober for quiz night at the Lord Nelson pub. When I was here in 2005-2006, I had a group of friends that coalesced around the weekly pub quiz, which we used to win on a regular basis (partly due to Donna’s formidable body of knowledge). This kind of quiz, involving trivia, science, sports, music, etc., is quite popular here. It was a great night, just like old times, with Alison, Donna, and me there for the beginning, Tim joining us partway through the quiz, and Alice coming by in time for the announcement that we had won, taking the L50 total of contestants’ one-pound entry fees.

I was especially pleased to see Spencer, who managed the Nelson during most of the time that I was here, and who, with co-quiz master John, came up with some pretty entertaining quizzes, including the legendary “During the war” round, with both of them dressed as old duffers in cloth caps and mufflers and puffing on pipes. Spencer doesn’t work at the Nelson anymore, so he was free to hang out, which we did until closing time.

When I was here before, I kept being baffled by how drunk I got on what didn’t seem a like very many beers. Then I realized that I had been thinking of “a beer” in terms of a 12-ounce American bottle. But in England I was drinking 20-ounce pints, and with a higher alcohol content than American beer. So “a beer” had roughly twice the kick I was used to.

THE BRITISH LIBRARY AND LOTS OF MAPS

On Wednesday I spent the afternoon in the Maps Reading Room at the British Library. My plans for research there were almost scuppered by having lost my wallet, including my driver’s license, a couple of weeks ago, since to get a reader’s pass, they require two different forms of ID to establish signature and address. Fortunately, though, they relented and gave me a week-long pass on the basis of my passport and a checkbook..

You can access the catalogue of materials on-line, either at the library or from afar, and request the materials you want to see. So I had quite a pile of original 17th century maps waiting for me, some in books, some in rolls, some folded into leather cases, some in giant portfolios. I’d seen some of them before, reproduced in books, but it was great to be able to look at the originals.

I wanted to get copies of some maps, and have been able to order a pretty satisfactory selection, but unfortunately, it wasn’t practical to get full copies of the big versions of two of the maps that I most wanted, because of their size and delicacy: Newcourt and Faithorne’s “An Exact Delineation of the Cities of London and Westminster and the Suburbs Thereof, Together with ye Burrough of Southwark and all the Through-Fares, Highwaies, Streetes, Lanes & Allies Within ye Same,” published in 1658, and the 1677 “A Large and Accurate Map of the City of London ichnographically describing all the streets, lanes, alleys, courts, yards, churches, halls and houses, &c., actually surveyed and delineated by John Ogilby, Esq., His Majesties Cosmographer.” The Newcourt map was a single sheet about 4 feet by 6 feet, and Ogilby’s is two sections, each of them comprised of about 25 or 30 pages of about 8x10 inches fitted together on a canvas backing, the whole thing folding to fit into a custom-made box.

I left the British Library with my head a bit too full of tiny pictures of houses and streets, and went to the National Portrait Gallery, which includes a couple of rooms of paintings of Charles II and his family, ministers, cronies, and other contemporaries. The only picture of Nell on display is not a very good one, but there is a great portrait of her hated rival Louise de Keroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth, and another of Charles’s other main mistress, Barbara Palmer, Duchess of Cleveland, posed rather blasphemously with her oldest illegitimate son by Charles as the Madonna and child. Nearby are also Samuel Pepys, James II (then Duke of York), the unfortunate James, Duke of Monmouth, Charles II’s oldest illegitimate son, who joined in an ill-advised plot to put him on the throne and died because of it, a galaxy of other people Nell would have known.

The National Portrait Gallery has computer terminals where you can search for portraits in their collection, and can print out black and white copies for free, or order color prints of varying sizes if you want to pay for them.

I went home by way of the “River Bus,” the commuter clipper that travels up and down the river. The civilized way to commute! And related to my research, as the river was a primary mode of travel in Nell’s time. I got on the boat at the Embankment Pier, very close to the location of the Privy Stairs, where Nell would have embarked to get to Charles’s apartments.

Alright. Enough for today. I’ll try to get up to date and post some pictures tomorrow!

Thursday, September 4, 2008

Fashion and Fire

Today I had a research appointment at the Museum of London (museumoflondon.org.uk), which I'd really been looking forward to. Hilary Davidson, Curator of Fashion and Decorative Arts, had pulled out several items of dress from Nell's lifetime (though not actually associated with her) - two pairs of stays (corsets, basically), a bodice front, two pairs of gloves, three pairs of shoes, a hat, three little gaming purses, two men's buff coats, and some beautiful pieces of lace. They were all carefully wrapped and padded, laid away in boxes, and displayed on a covered table, and Hilary handled them gently with gloves on. I was allowed to take pictures, but had to agree not to publish any, not even on my humble little blog!

Nevertheless, it was amazing to see up close actual surviving pieces of clothing from the mid to late 17th century. Seeing the inside of a set of stays stained by sweat and dirt brings the wearer so close you can almost feel her. I could imagine Nell being enchanted by a tiny purse with little red hearts woven into its fabric, a pair of soft leather gloves decorated with a deep fringe of looped carnation-colored ribbon, a pair of red velvet mules elaborately embroidered with real silver, and with a heel in a style that has become fashionable again.

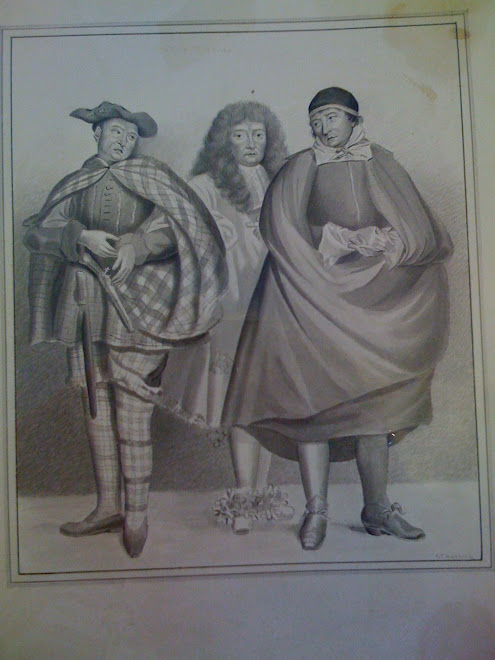

One of the most striking pieces was one of the buff coats. I included a picture yesterday of a buff coat from the V&A collection - a plain one, like soldiers would wear. This coat was a different creature altogether. The leather was finer and softer, and it was elegantly tailored, with flaring coat-tails, slitted for a sword hilt. The sleeves, facings, and pockets were heavily worked with silver, in a pattern that Hilary remarked had Eastern influences. Perhaps the wearer had just returned from a Grand Tour and wanted something exotic.

Two other people were conducting research while I was there -- Ninya Mikhaila and Jane Malcolm-Davies, authors of The Tudor Tailor: Reconstructing Sixteenth Century Dress (tudortailor.com). They're at work on their next book, focusing on less grand, day-to-day clothes of the period. They had laid out a sailor's linen smock, stained brown with tar and age, and a giant tray of flat brown caps, which they refer to as "cowpat caps." They're apparently cataloguing all of them, and there seem to be more than you would think! While I was there they finished with one set of about six or eight and helped bring out the next large cloth-lined drawer of more, including one tiny and unbearably cute one for a little baby.

I commented that I bet they would get a lot of business from Renaisance Faire participants, and they said that yes, a lot of their sales did come from the U.S. and particulary California. They were amused to hear that I'd spent many years working Renaissance Faires and had spent almost as much time in sixteenth century clothes as twentieth. Almost.

I also walked through the rest of the museum, which includes day-to-day objects and information about the daily lives of Londoners through the millenia. Much of the museum is closed for renovations right now (and I just got in under the wire with the costumes; in two weeks they won't be accessible for several months), so the main display only went up to 1666. But that's good, because it's smack in the middle of my period.

Fortuitously, the museum also has a special exhibit right now called "London Burning," about the Great Fire of London, which burned from September 2-5, 1666. So there I was, right in the middle of the 342nd anniversary of the fire. There were objects from the period, reproductions of paintings of the fire, maps of the damaged areas, prints of the various proposed rebuilding plans, a fireman's helmet of the period (looking astonishingly like what firemen still wear), and much more.

Particularly nice was a little soundscape, featuring ballads of the period, one about the Rump Parliament and the return of Charles II, and the other about the fire being divine retribution for sinfulness, as well as the cries of street peddlars.

To get to the museum, I walked from the Bank underground station west along Mansion House, Poultry, Cheapside, and Newgate Street, and then up St. Martin Le Grand. I walked that route hundreds of times when I was here before because it was also the way to St. Bartholomew's Hospital, where my mother spent a lot of time. There's been a hospital there since 1123, and some of it has even been rebuilt since then!

Cheapside is one of the oldest of London's streets, and the streets branching off it - Bread Street, Honey Lane, and the nearby Poultry - reflect the area's long history as a market place ("cheap" means a market). St. Paul's Cathedral is just south of where Cheapside turns into Newgate Street. Further east along Cheapside stands the church of St. Mary le Bow. The present building, built 1671-1673, with its steeple completed in 1680, is one of 51 churches that were designed by Christopher Wren, and built to replace those burned in the Great Fire. You can see pictures of them at http://www.flickr.com/photos/stevecadman/sets/72157594356228263.) The saying that a true Cockney is someone born within the sound of Bow Bells refers to this church. Of course its bells would have been audible much further away before the city got quite so loud.

Nevertheless, it was amazing to see up close actual surviving pieces of clothing from the mid to late 17th century. Seeing the inside of a set of stays stained by sweat and dirt brings the wearer so close you can almost feel her. I could imagine Nell being enchanted by a tiny purse with little red hearts woven into its fabric, a pair of soft leather gloves decorated with a deep fringe of looped carnation-colored ribbon, a pair of red velvet mules elaborately embroidered with real silver, and with a heel in a style that has become fashionable again.

One of the most striking pieces was one of the buff coats. I included a picture yesterday of a buff coat from the V&A collection - a plain one, like soldiers would wear. This coat was a different creature altogether. The leather was finer and softer, and it was elegantly tailored, with flaring coat-tails, slitted for a sword hilt. The sleeves, facings, and pockets were heavily worked with silver, in a pattern that Hilary remarked had Eastern influences. Perhaps the wearer had just returned from a Grand Tour and wanted something exotic.

Two other people were conducting research while I was there -- Ninya Mikhaila and Jane Malcolm-Davies, authors of The Tudor Tailor: Reconstructing Sixteenth Century Dress (tudortailor.com). They're at work on their next book, focusing on less grand, day-to-day clothes of the period. They had laid out a sailor's linen smock, stained brown with tar and age, and a giant tray of flat brown caps, which they refer to as "cowpat caps." They're apparently cataloguing all of them, and there seem to be more than you would think! While I was there they finished with one set of about six or eight and helped bring out the next large cloth-lined drawer of more, including one tiny and unbearably cute one for a little baby.

I commented that I bet they would get a lot of business from Renaisance Faire participants, and they said that yes, a lot of their sales did come from the U.S. and particulary California. They were amused to hear that I'd spent many years working Renaissance Faires and had spent almost as much time in sixteenth century clothes as twentieth. Almost.

I also walked through the rest of the museum, which includes day-to-day objects and information about the daily lives of Londoners through the millenia. Much of the museum is closed for renovations right now (and I just got in under the wire with the costumes; in two weeks they won't be accessible for several months), so the main display only went up to 1666. But that's good, because it's smack in the middle of my period.

Fortuitously, the museum also has a special exhibit right now called "London Burning," about the Great Fire of London, which burned from September 2-5, 1666. So there I was, right in the middle of the 342nd anniversary of the fire. There were objects from the period, reproductions of paintings of the fire, maps of the damaged areas, prints of the various proposed rebuilding plans, a fireman's helmet of the period (looking astonishingly like what firemen still wear), and much more.

Particularly nice was a little soundscape, featuring ballads of the period, one about the Rump Parliament and the return of Charles II, and the other about the fire being divine retribution for sinfulness, as well as the cries of street peddlars.

To get to the museum, I walked from the Bank underground station west along Mansion House, Poultry, Cheapside, and Newgate Street, and then up St. Martin Le Grand. I walked that route hundreds of times when I was here before because it was also the way to St. Bartholomew's Hospital, where my mother spent a lot of time. There's been a hospital there since 1123, and some of it has even been rebuilt since then!

Cheapside is one of the oldest of London's streets, and the streets branching off it - Bread Street, Honey Lane, and the nearby Poultry - reflect the area's long history as a market place ("cheap" means a market). St. Paul's Cathedral is just south of where Cheapside turns into Newgate Street. Further east along Cheapside stands the church of St. Mary le Bow. The present building, built 1671-1673, with its steeple completed in 1680, is one of 51 churches that were designed by Christopher Wren, and built to replace those burned in the Great Fire. You can see pictures of them at http://www.flickr.com/photos/stevecadman/sets/72157594356228263.) The saying that a true Cockney is someone born within the sound of Bow Bells refers to this church. Of course its bells would have been audible much further away before the city got quite so loud.

Wednesday, September 3, 2008

Cambridge and the V&A Museum

On Monday, September 1, I made a trip by train to Cambridge, to have dinner with someone who was very important to my mother in the last couple of years of her life, and in mine while I was here caring for her - her vicar, Martin Seeley.

He was formerly the vicar of Christ Church here on the Island, and while my mother didn't know him until she was too ill to go to his church, he visited her regularly at home, in hospitals, the nursing home, and the hospice, as well as giving her the last rites the night before she died and performing her funeral service. And he was a shoulder for me to lean on more than once when the fear and sadness and loneliness were overwhelming.

Two years ago Martin and his family moved to Cambridge because he had been sought after and hired for a very prestigious new post, as head of a school connected with the university. So now he is The Reverend Canon Martin A. Seeley, President, Westcott House, Jesus Lane, Cambridge!

I had only briefly crossed paths with Martin's wife Jutte (sorry - I'm only guessing at the spelling), who is also a minister, and their charming children, Anna and Luke. We had a lovely dinner (courtesy of my generous Uncle Al) at Fort St. George, a pub right on the bank of the River Cam, and on the evocatively named Midsummer Common.

Before dinner, I spent a couple of hours walking around the old streets of Cambridge and marveling at the ancient colleges (Trinity was centuries old when Samuel Pepys went there in the 17th century) but certainly didn't give it the time it deserved.

After dinner, Martin showed me the chapel and grounds of Jesus College, where he had been an undergraduate, and walked me to where I could get the bus to the train station.

It was great to see Martin and his family, and yes, there is a Nell Gwynn connection. In the last few years of her life, Nell became friends with Thomas Tenison, then vicar of St. Martin in the Fields, and later Archbishop of Canterbury. He helped her make charitable donations (usually anonymously); attended her friend James, Duke of Monmouth, at his hideously botched execution; visited, counseled, and comforted Nell when she had had two strokes and was dying (possibly from syphilis); and gave her funeral service at St. Martin in the Fields.

I told Martin I'd value his advice and input on what Dr. Tenison would have told Nell in those later years. She certainly didn't have any religious upbringing and her life, though nothing out of the ordinary by the standards of Charles II's court, wasn't quite in keeping with what was respectable by Christian standards. The death of her youngest son James at the age of eight must have shaken her world and made her think about the afterlife and her own life as she had never done before. And the years following were no easier, as a succession of her closest friends died, finally followed by the King, to whom she had been a faithful lover for seventeen years and borne two children.

I also told Martin about my search for Nell's grave at St. Martin in the Fields. He asked if I knew the vicar there. Um, no, I haven't had the pleasure. And he kindly offered to put me in touch!

Today I met my friend Donna for lunch at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where she is a senior metal conservator, and then I spent the afternoon going through the British Gallery, with furniture, household items, clothes, paintings, sculpture, and technology from the seventeenth century; and then looking at glass and silver from the same time. I already know a fair amount about daily life during Nell's lifetime, but there is nothing quite like seeing the actual suit that Charles II's brother James, the Duke of York (and later James II), wore at his wedding, or a delicate leather fan of the period with an inctricate landscape painted on it, or feeling samples of the rope support and various layers of mattresses and covers that a bed in a wealthy household of the period would have had.

He was formerly the vicar of Christ Church here on the Island, and while my mother didn't know him until she was too ill to go to his church, he visited her regularly at home, in hospitals, the nursing home, and the hospice, as well as giving her the last rites the night before she died and performing her funeral service. And he was a shoulder for me to lean on more than once when the fear and sadness and loneliness were overwhelming.

Two years ago Martin and his family moved to Cambridge because he had been sought after and hired for a very prestigious new post, as head of a school connected with the university. So now he is The Reverend Canon Martin A. Seeley, President, Westcott House, Jesus Lane, Cambridge!

I had only briefly crossed paths with Martin's wife Jutte (sorry - I'm only guessing at the spelling), who is also a minister, and their charming children, Anna and Luke. We had a lovely dinner (courtesy of my generous Uncle Al) at Fort St. George, a pub right on the bank of the River Cam, and on the evocatively named Midsummer Common.

Before dinner, I spent a couple of hours walking around the old streets of Cambridge and marveling at the ancient colleges (Trinity was centuries old when Samuel Pepys went there in the 17th century) but certainly didn't give it the time it deserved.

After dinner, Martin showed me the chapel and grounds of Jesus College, where he had been an undergraduate, and walked me to where I could get the bus to the train station.

It was great to see Martin and his family, and yes, there is a Nell Gwynn connection. In the last few years of her life, Nell became friends with Thomas Tenison, then vicar of St. Martin in the Fields, and later Archbishop of Canterbury. He helped her make charitable donations (usually anonymously); attended her friend James, Duke of Monmouth, at his hideously botched execution; visited, counseled, and comforted Nell when she had had two strokes and was dying (possibly from syphilis); and gave her funeral service at St. Martin in the Fields.

I told Martin I'd value his advice and input on what Dr. Tenison would have told Nell in those later years. She certainly didn't have any religious upbringing and her life, though nothing out of the ordinary by the standards of Charles II's court, wasn't quite in keeping with what was respectable by Christian standards. The death of her youngest son James at the age of eight must have shaken her world and made her think about the afterlife and her own life as she had never done before. And the years following were no easier, as a succession of her closest friends died, finally followed by the King, to whom she had been a faithful lover for seventeen years and borne two children.

I also told Martin about my search for Nell's grave at St. Martin in the Fields. He asked if I knew the vicar there. Um, no, I haven't had the pleasure. And he kindly offered to put me in touch!

Today I met my friend Donna for lunch at the Victoria and Albert Museum, where she is a senior metal conservator, and then I spent the afternoon going through the British Gallery, with furniture, household items, clothes, paintings, sculpture, and technology from the seventeenth century; and then looking at glass and silver from the same time. I already know a fair amount about daily life during Nell's lifetime, but there is nothing quite like seeing the actual suit that Charles II's brother James, the Duke of York (and later James II), wore at his wedding, or a delicate leather fan of the period with an inctricate landscape painted on it, or feeling samples of the rope support and various layers of mattresses and covers that a bed in a wealthy household of the period would have had.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)